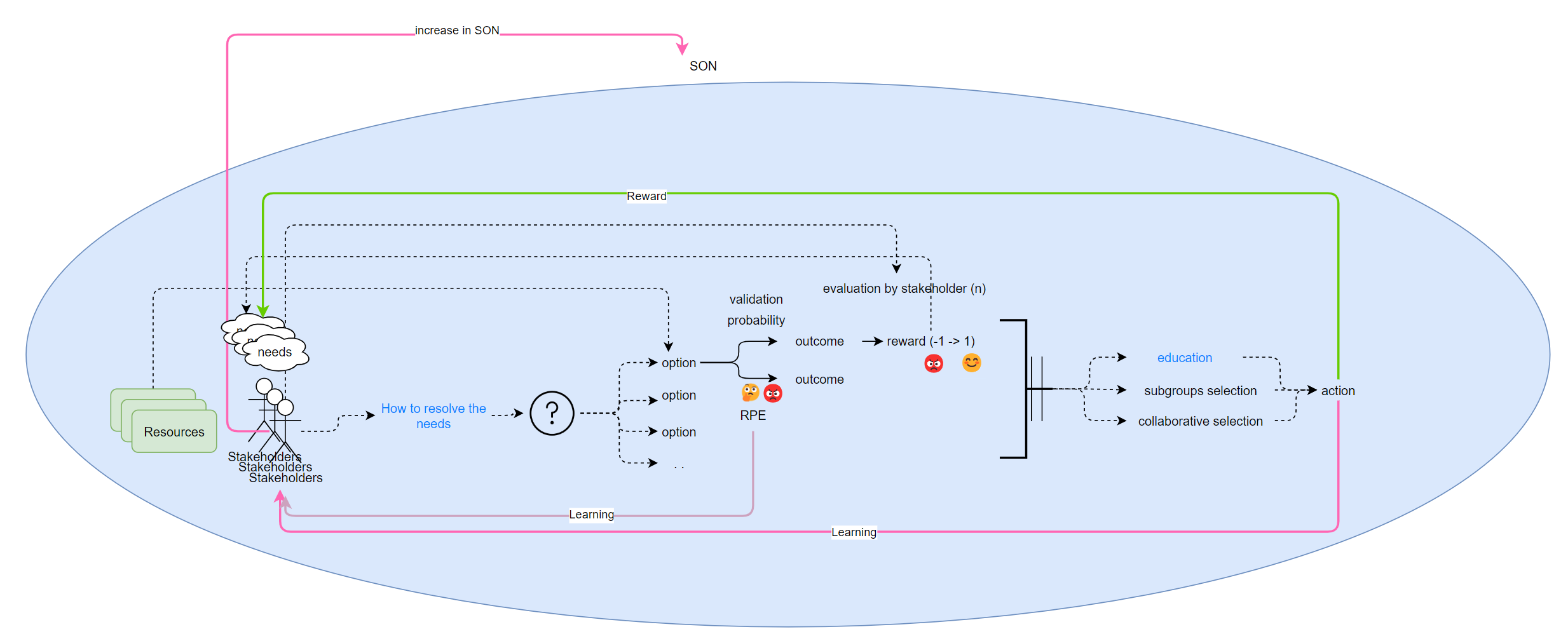

Mechanistic Model for Decision Making

I will suggest that decision-making has several mental elements that work together to produce a decision. These are the elements:

Contents

Elements

Need

Every decision starts with a need or needs. Need is a biological process in the brain, signaling that there is a lack of some resources. The resources may be physical resources or emotional resources. From a psychological perspective see Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

Stakeholders

stakeholders are the members of the organization that may be affected by the decision may or non-members that may be affected by the organization's actions.

Question

A question is a mental tool that help gather information and start a decision process, on how to fulfill the need.

Options

A need can be fulfilled in many ways. Every way is an “option”.

Mental Objects Network

The options are an implementation of theories the brain holds about the world. These theories are connected with each other and describe how the world works and what we can do to change our surroundings. We use these theories to change the surrounding so our needs will be fulfilled. The network of theories is built from mental objects representing of the world, and therefore will be called Mental Objects Network (MON). For further explanation, see epistemology.

Outcomes

For every ‘’option’’ there are outcomes. Some of the outcomes may fulfill the ‘’need’’, and some may have side effects.

Resources

Every option consume some resources. Therefore, when calculating the values of each option, the resources should also be calculated.

Value

The outcomes have an effect on our physical or emotional resources. They carry a value. The value may be rewarding, neutral or taxing. The Magnitude of the value can also vary from none to fatal in taxing value or from none to overwhelming good, in positive values.

Probability of success

Every option has some chances to succeed. Every option is constructed from a cascade of events, and every event has some probability to happen. It may depend on the known probabilities of an event to happen (for instance we may assume that our chances of winning the lottery have a probability of 1 to a million), or the level of corroboration (the number of times we tested the theory). The more we corroborated the theory we may have more confidence we can predict her chance to occur (from an epistemological perspective we do not have any way to predict the future, bet let’s leave this for now). Consequently, when an option has many steps (events that should occur in order for her to succeed), or/and when the events are not well tested, the probability of success drops.

Resources

For every action, which is based on the option we selected, there is a tax on our resources. Before we evaluate options, we should also consider how much resources do we have, and if we have the specific resources needed for the option.

Evaluation

When we have to choose from a set of options, we should evaluate every option total outcomes values, the resource it demands, and the probability of success.

Selection

We should compare the total value of every options and choose the best value. Yet for many reasons we will discuss later, we may not evaluate at all, or choose the option we are more familiar with, even if there are better options. The selection of an option, is called also decision

Action

Every selection should be followed by actions designed in the selection phase.

Learning

We learn from hypothesizing and from doing. Learning through the decision process and from the doing is crucial for developing corroborated SON. corroborated SON is the base for our ability to predict well. The SON is built from theories we are building and testing throughout our entire life. We learn from others, or we conjecture about how things work. We may then test the theories, and see if they are false or corroborate (see Karl Popper on terminology[1]).

See also

References

- ↑ Popper, K. (2002). The Logic of Scientific Discovery (Routledge Classics). Routledge.