Difference between revisions of "Epistemology"

From Deliberative Democracy Institiute Wiki

(→The Foundations of Knowledge) |

(→Simplicity and Induction) |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

Although this statement may be true it can not tell us nothing about the next occasion of breaking glass. If we will test it and we will find that next time we will hear a different sound, we might say that "All breaking glasses so far observed has this specific sound, while the last had another sound"''. By describing the relations between the phenomena in a descriptive mode, we may reach very fast to infinite numbers of description. So yet again for the sake of simplicity, we will try to describe the relations as inductions. | Although this statement may be true it can not tell us nothing about the next occasion of breaking glass. If we will test it and we will find that next time we will hear a different sound, we might say that "All breaking glasses so far observed has this specific sound, while the last had another sound"''. By describing the relations between the phenomena in a descriptive mode, we may reach very fast to infinite numbers of description. So yet again for the sake of simplicity, we will try to describe the relations as inductions. | ||

| − | Inductions are | + | Inductions are relations, assumed to be constant regardless of time or place, between phenomena. In our example, we will say that "Always, when a glass brakes it has specific sound" ("broken glass sound"). Due to the ''Phenomenological cage principal'', we are unable to check that this relation is always true. What we can do, is to try to test it in every occasion the one of the phenomena occur, and to see if it is still stand, or was the induction refuted<ref>Popper, K. (2002). The Logic of Scientific Discovery (Routledge Classics) (p. 544). Routledge.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | When an induction is being refuted, we should try to suggest new relation, this time more complex, to describe the relations that will be true for '''every observation we have seen so far'''. This new induction will be tested again and again, and after every refutation, a new relation will be conjecture and will be tested, when every new induction should describe every observation we had so far. | ||

Revision as of 11:42, 2 December 2012

This page is Under Constraction. It may have low level of English and low methodological coherency. Please comeback later {{{1}}} |

| |

The Foundations of Knowledge

The phenomenological cage

The first question I want to address, is why most of us have different perceptions about the world. Why it is hard to agree on things. I'll propose that if we will undestand how knowledge is constucted in the brain, we will have more understanding in the question.

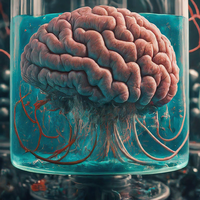

Knowledge is our understanding and predicting the behavior of the world within us and around us. Each and every one of has have unique perception. How this perception is created and how it realte to the “real world” is the quest that epistemology has set before herself. Yet for more then 2500 years of epistemology, nobody had found a reliable way to establish the relations of perception or knowing about the “real world”. To demonstrate the problem of knowledge, we may use the “brain in a vat” (Link to wikipedia) thought experiment. In this thought experiment, you are asked to find a reliable way to know if you really exists as you perceive it, or you are actually a brain in a vat, which gets it's sensory inputs from a computer, that simulate the perceived world.

Till today nobody was able to find a reliable answer to this question. People sometime suggest that Hillary Putnaham had found a way, but her conclusions say otherwise. (ref) she conclude that we can not distinguish between realty and virtual experience.

Therefore, we have to set for now an axiom that says:

- “We can not have any knowledge about the inner or outer-world”. Or in Kant's methodology, we will never know the noumenon.

The only thing we can say is that we observe phenomena. We have some idea of the world as we perceive it. How this representation is constructed, we will have to suggest. This principle will be called "The phenomenological cage principle".

Philosophers had tried since Hume and Kant to describe the inner mechanisms that constructed our perception, but no final solution was achieved. So to solve this problem I will use ideas that were taken from neurophysiology, and may comply to the philosophic literature.

Creating of order in the Brain/Mind

The Phenomena

Kant described the inputs that the mind perceives through the senses as “phenomena”. The phenomena are inputs that our senses gets from unknown sources. In the equivalent brain model, our senses get their inputs from sensory receptors.

Propensities in the phenomena (Or order in the phenomena)

When nothing controls the phenomena we may accept that it will have no order, but when there is something that control the phenomena we may except to find some order in it[1]. But even if not so, the brain/mind will assume so.

The Similarity

The mind assume similarity between phenomena or sensory inputs when they are closely matched order of phenomena. In a philospohical manner it is hard to define similarity in phenomena. For some solution you can go to Churchland[2]. When using neurons we can say that when signals from the same sets of receptors or from same set of sensory objects occur simultaneously, they will initiate an LTP[3] somewhere down the neural-networks, and will cause induction or LTP between the set of receptors or the set of sensory objects. In an optimal repetitions temporally sequence of similar inputs, the LTP will be strengthen.

Simplicity and Induction

The relation between two similar phenomena might be very simple. They may be linked directly. For instance, A sound of a broken glass may be directly connected to a braking glass. But it can be connected in more complex way, for instance there may be some computer that create a breaking sound, whenever I see a breaking glass. Or this connection may be correct until some time, ans it may be wrong in some future time[4]. The reason to chose the most simple connection is because the number of available possible relations between a sound and a breaking glass are infinite. Therefore for reasons of effective storage, we will use the simplest solution available, which will be "All breaking glasses so far observed has this specific sound".

Although this statement may be true it can not tell us nothing about the next occasion of breaking glass. If we will test it and we will find that next time we will hear a different sound, we might say that "All breaking glasses so far observed has this specific sound, while the last had another sound". By describing the relations between the phenomena in a descriptive mode, we may reach very fast to infinite numbers of description. So yet again for the sake of simplicity, we will try to describe the relations as inductions.

Inductions are relations, assumed to be constant regardless of time or place, between phenomena. In our example, we will say that "Always, when a glass brakes it has specific sound" ("broken glass sound"). Due to the Phenomenological cage principal, we are unable to check that this relation is always true. What we can do, is to try to test it in every occasion the one of the phenomena occur, and to see if it is still stand, or was the induction refuted[5]

When an induction is being refuted, we should try to suggest new relation, this time more complex, to describe the relations that will be true for every observation we have seen so far. This new induction will be tested again and again, and after every refutation, a new relation will be conjecture and will be tested, when every new induction should describe every observation we had so far.

But we will try to constantly refute it, to see if it still holds.

This

Other Asspects of Epistemology

Bush and Mosteller Learning Curve

This section was mostly taken from Paul W. Glimcher1 paper in PNAS[6]

This very general idea of Conditional learning, was first mathematically formalized when Bush and Mosteller[7], 24) proposed that the probability of Pavlov's[8] dog expressing the salivary response on sequential trials could be computed through an iterative equation where

In this equation, Anext_trial is the probability that the salivation will occur on the next trial (or more formally, the associative strength of the connection between the bell and salivation). To compute Anext_trial, one begins with the value of A on the previous trial and adds to it a correction based on the animal's experience during the most recent trial. This correction, or error term, is the difference between what the animal actually experienced (in this case, the reward of the meat powder expressed as Rcurrent_trial) and what he expected (simply, what A was on the previous trial). The difference between what was obtained and what was expected is multiplied by α, a number ranging from 0 to 1, which is known as the learning rate. When α = 1, A is always immediately updated so that it equals R from the last trial. When α = 0.5, only one-half of the error is corrected, and the value of A converges in half steps to R. When the value of α is small, around 0.1, then A is only very slowly incremented to the value of R.

What the Bush and Mosteller[9][10] equation does is compute an average of previous rewards across previous trials. In this average, the most recent rewards have the greatest impact, whereas rewards far in the past have only a weak impact. If, to take a concrete example, α = 0.5, then the equation takes the most recent reward, uses it to compute the error term, and multiplies that term by 0.5. One-half of the new value of A is, thus, constructed from this most recent observation. That means that the sum of all previous error terms (those from all trials in the past) has to count for the other one-half of the estimate. If one looks at that older one-half of the estimate, one-half of that one-half comes from what was observed one trial ago (thus, 0.25 of the total estimate) and one-half (0.25 of the estimate) comes from the sum of all trials before that one. The iterative equation reflects a weighted sum of previous rewards. When the learning rate (α) is 0.5, the weighting rule effectively being carried out is an exponential series, the rate at which the weight declines being controlled by α.

When α is high, the exponential function declines rapidly and puts all of the weight on the most recent experiences of the animal. When α is low, it declines slowly and averages together many observations, which is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig 1: “Weights determining the effects of previous rewards on current associative strength effectively decline as an exponential function of time”[11].

The Bush and Mosteller equation was critically important, because it was the first use of this kind of iterative error-based rule for reinforcement learning; additionally, it forms the basis of all modern approaches to this problem. This is a fact often obscured by what is known as the Rescorla–Wagner model of classical conditioning[12]>. The Rescorla–Wagner model was an important extension of the Bush and Mosteller approach to the study of what happens to associative strength when two cues predict the same event. Their findings were so influential that the basic Bush and Mosteller rule is now often mistakenly attributed to Rescorla and Wagner by neurobiologists.

References

<references>- ↑ Popper, K. (1997). World of Propensities (p. 60). Thoemmes Press.

- ↑ Paul M. Churchland. (2012). Plato’s Camera: How the Physical Brain Captures a Landscape of Abstract Universals. MIT Press.

- ↑ Teyler, T. J., & DiScenna, P. (1987). Long-term potentiation. Annual review of neuroscience, 10, 131–61.

- ↑ Goodman, N., & Putnam, H. (1983). Fact, Fiction, and Forecast, Fourth Edition (p. 160). Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Popper, K. (2002). The Logic of Scientific Discovery (Routledge Classics) (p. 544). Routledge.

- ↑ Glimcher, P. W. (2011). Understanding dopamine and reinforcement learning: the dopamine reward prediction error hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108 Suppl (Supplement_3), 15647–54.

- ↑ Bush RR, Mosteller F (1951) A mathematical model for simple learning. Psychol Rev 58:313–323

- ↑ Pavlov IP (1927) Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex (Dover, New York).

- ↑ Bush RR, Mosteller F (1951) A mathematical model for simple learning. Psychol Rev 58:313–323

- ↑ Bush RR, Mosteller F (1951) A model for stimulus generalization and discrimination. Psychol Rev 58:413–423.

- ↑ Schoenbaum G, Roesch MR, Stalnaker TA, Takahashi YK (2009) A new perspective on the role of the orbitofrontal cortex in adaptive behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:885–892.

- ↑ Rescorla RA, Wagner AR (1972) in Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory, A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement, eds Black AH, Prokasy WF (Appleton Century Crofts, New York), pp 64–99.